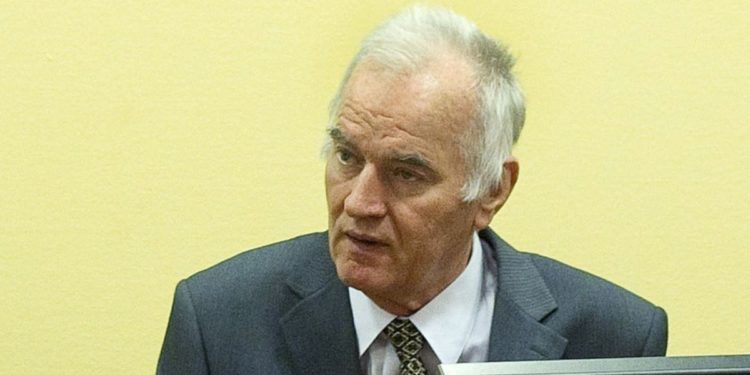

The Bosnian Serb general Ratko Mladić, nicknamed “the butcher of the Balkans” by a certain type of press already before he was convicted of genocide and sentenced to life imprisonment by the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) for his leading role in the genocide after the fall of Srebrenica in 1995 (when thousands of Bosnian Muslims were killed by his troops), will appear before a newly composed Appeals Chamber of UN judges for the first time on Tuesday. A majority of them – three of the five – are African women, one of whom is presiding. Almost all judges (4 of the 5) are Africans. All of them are black (The fifth judge is a Jamaican). In the name of the UN and thus in the name of all humankind, they will give the final judgment about the role of a white general as (according to the first instance conviction) the main person responsible for the worst atrocity and the only genocide in Europe since the Second World War.

So what? Many argue that country of origin and colour of the skin should not be of importance when you work for the UN or a court that represents a community of more than 120 states like the International Criminal Court. You then work for and represent the international community as a whole – which is, of course, completely true, and it was completely justified when, for example, ICTY staff members refused to reveal their nationality to curious journalists.

On the other hand, the ICC has often been criticized as a ‘European court for Africa’, not only because it is based in The Hague, but also because (more than) half of the judges, for a long time, were from Europe.

The inequality of opportunities to work for the ICC has been noted.

But it can be the other way round, too, before a UN court. Judges from Zambia, Gambia/Zimbabwe, Burkina Faso, Uganda and Jamaica will give the final judgment about the person most responsible for the worst white man’s crime in Europe since 1945.

Those black judges will be there because of their outstanding legal qualifications and their years of experience in international courts, see bios below. According to statutory requirements, international court judges must also be elected with regard to their high moral character which should allow them to perform their important duties independently from political pressure or personal interest.

Of course, it must be absolutely clear that race has nothing to do with legal qualifications or personal character – and that is why, in the long term and in an ideal world, race must be completely disregarded in the debate about who should judge whom in international courts.

In the short term and in the real world, African lawyers have not had equal opportunities in international courts because they have not been prepared for such jobs in sufficiently large numbers. The European Union used to have a programme for good African law students to come and do paid internships at the ICC. Unfortunately, this program has been abolished. Such grants must be reinstated in larger numbers. Supporting the good interns of today means breeding the good judges for the future.

The Newly Composed Appeals Chamber in the Mladić Case:

Judge Ms. Prisca Matimba Nyambe (Zambia), Presiding

Judge Ms. Aminatta Lois Runeni N’gum (Gambia/Zimbabwe)

Judge Mr. Gberdao Gustave Kam (Burkina Faso)